p.7 A Terrible Beauty… James Dunnett

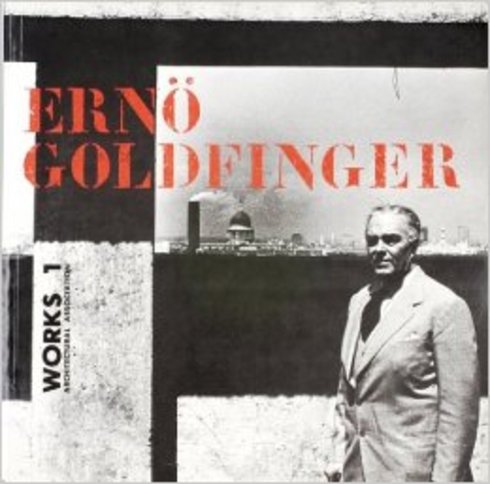

'The client does not care about architecture, he cares whether the building works. The architecture is my own private pleasure,' Goldfinger has said. The practicality of this remark, and also its bitterness, are essential to his work; but it is time - now that he has reached his eighties - to make the private pleasure public. I can only offer a subjective response to an architecture that can seem both beautiful and terrifying in its implications.

The moral basis of Goldfinger's architecture as of all those who, like him, were closely involved with CIAM, was the detailed consideration of the environmental conditions conducive to human welfare - whether their analysis is now thought to have been complete or not. The high-rise housing schemes which he built for the GLC were a product of this consideration in every detail, designed to secure 'sun, space, and greenery' for their inhabitants. But in Goldfinger's hands the millenial utopian vision has acquired an air of menace, the ideal has been pushed to its very limits.

The sheer scale and drama of their architecture are exciting, but unnerving. Exciting because the control of form is so complete. The rhythms of the facades, founded on the mathematical control of proportion, are a statement of formal architectural values unequalled in this country, I would say, since Lutyens, a perfect resolution of horizontal and vertical elements. Raw concrete has rarely seemed so beautiful, its detailing handled with a knowledge beginning with Perret. The sequence of space and form is varied, picturesque, never repetitive: under a low evening sun one has the feeling of participation in an heroic landscape.

But it is unnerving not only because of scale - 28 storeys at Rowlett Street, 30 at Edenham Street - but because of the choice of elements of a distinctly minatory character. lt is as though Goldfinger, from among the Functionalist totems, had chosen as a source of inspiration the artefacts of war. The sheer concrete walls of the circulation towers are pierced only by slits; cascading down the facade like rain, they impart a delicate sense of terror. At the summit of the tower the boiler house is cantilevered far out; with its ribbon glazing and surmounted by flues it evokes the bridge of a warship. At night the estate is illuminated by the merciless beam of powerful arclights mounted at the summit of the slab.

The office complex at the Elephant and Castle reflects the same spirit. The proportional textures of the facades are calculated with perfect understanding, the logic of the structural frame expressed with an insistence unequalled even by Mies; the skyline - as always - underlined by a cornice. But the dour streaked concrete, the jagged pyramidal massing, the slit windows, again have the terrifying connotations of ‘security’.

It is tempting to try and laugh this off as a kind of grim romanticism, the theatrical ‘castle-like air’ to which Vanbrugh was addicted. But one is uncomfortably aware that it has to be taken seriously. Its nearest architectural parallels (‘source’ may be too strong a word) seem to be the giant Constructivist projects for administrative buildings of the 1920s and indeed one has a feeling that this is Stalin’s architecture as it should have been. Is this then the image of the totalitarian perversion of that quest for welfare which was central to the Modern Movement? As the current home of the British state welfare - the Department of Health and Social Security - this would perhaps not be wholly inappropriate.

But it would be wrong to press this point too far. The intellectual power required to create a significant work of art can often seem frightening to others. It requires strength to be inspired by it and not run for cover. Goldfinger's is a demanding architecture, whose place is at the centre of intellectual life.

The high-rise housing schemes which he built for the GLC were a product of this consideration in every detail, designed to secure 'sun, space, and greenery' for their inhabitants... But in Goldfinger's hands the millenial utopian vision has acquired an air of menace, the ideal has been pushed to its very limits.

The sheer scale and drama of their architecture are exciting, but unnerving. Exciting because the control of form is so complete. The rhythms of the facades, founded on the mathematical control of proportion, ore a statement of formal architectural values unequalled in this country, l would say, since Lutyens, a perfect resolution of horizontal and vertical elements. Raw concrete has rarely seemed so beautiful, its detailing handled with a knowledge beginning with Perret. The sequence of space and form is varied, picturesque, never repetitive: under a low evening sun one has the feeling of participation in an heroic landscape.

But it is unnerving not only because of scale - 28 storeys at Rowlett Street, 30 at Edenham Street - but because of the choice of elements of a distinctly minatory character. lt is as though Goldfinger, from among the Functionalist totems, had chosen as a source of inspiration the artefacts of war. The sheer concrete walls of the circulation towers are pierced only by slits; cascading down the facade like rain, they import a delicate sense of terror. At the summit of the tower the boiler house is cantilevered far out; with its ribbon glazing and surmounted by flues it evokes the bridge of a warship. At night the estate is illuminated by the merciless beam of powerful arclights mounted at the summit of the slab.

…

The intellectual power required to create a significant work of ort can often seem frightening to others. lt requires strength to be inspired by it and not run for cover. Goldfinger's is a demanding architecture, whose place is at the centre of intellectual life.