James Dunnett, 'The Ecstacy of Space - A response to a week spent at Ernö Goldfinger's Balfron Tower in October 2014, DOCOMOMO-UK, Winter 2014, pp. 8-9

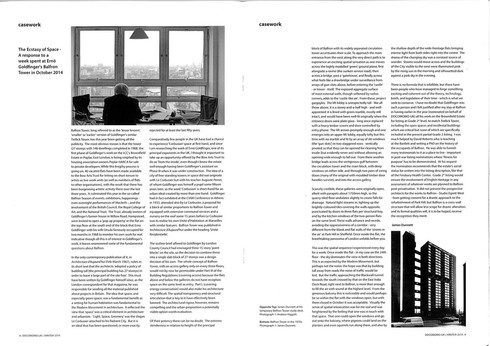

Balfron Tower, long referred to as the 'lesser known', 'smaller' or 'earlier' version of Goldfinger's similar Trellick Tower, has this year been getting all the publicity. The most obvious reason is that the tower (27 storeys with 146 dwellings completed in 1968, the first phase of Goldfinger’s work on the LCC's Brownfield Estate in Poplar, East London is being emptied by its housing association owners Poplar HARCA for sale to private developers. While this lengthy process is going on, 40 vacated flats have been made available to the Bow Arts Trust for letting on short tenure to artists as live-work units (as well as numbers of flats to other organisations), with the result that there has been burgeoning artistic activity there over the last three years. It culminated this year in the so-called Balfron Season of events, exhibitions, happenings - even overnight performances of Macbeth -, and the involvement of the British Council, the Royal College of Art, and the National Trust. The Trust, already owners of Goldfinger's former house in Willow Road, Hampstead, were invited to open a 'pop up property’ in the flat on the top floor at the south end of the block that Erno Goldfinger with his wife Ursula famously occupied for two months in 1968 to monitor his own work for real. Indicative though all this is of interest in Goldfinger's work, it leaves unanswered some of the fundamental questions about Balfron.

In the only contemporary publication of it, in Architecture d'Aujourd'hui (Feb-March 1967), notes in its short text that the architects ‘adopted a policy of building tall (the principal building has 27 storeys) in order to leave a large part of the site free’. This must have been written by Goldfinger himself since, as the London correspondent for that magazine, he was responsible for sending all the material published about projects in Britain. The idea that space, and especially green space, was a fundamental benefit as a setting for human habitation was fundamental to the Modern Movement in architecture. It reflected the view that 'space' was a critical element in architecture and urbanism – ‘Light, Space, Greenery’ was the slogan Le Corbusier attached to his Radiant City. But it is an ideal that has been questioned, or more exactly, rejected for at least the last fifty years.

Comparatively few people in the UK have had a chance to experience 'Corbusian' space at first hand, and since I am researching the work of Ernö Goldfinger, one of its principal exponents in the UK, I thought it important to take up an opportunity offered by the Bow Arts Trust to do so ‘from the inside’, even though I knew the estate well enough having been Goldfinger's assistant on Phase III when it was under construction. The idea of a city of free-standing towers in space did not originate with Le Corbusier but with his teacher Auguste Perret, of whom Goldfinger was himself a pupil some fifteen years later, so the word 'Corbusian’ is short-hand for an urban ideal created by more than one hand. Goldfinger had in fact exhibited at the CIAM Conference in Athens in 1933, attended also by Le Corbusier, a proposal for block of similar proportions to Balfron Tower and equipped with extensive communal services and a nursery on the roof some 15 years before Le Corbusier was to realise his own Unité d'Habitation at Marseilles with similar features. Balfron Tower was published in Architecture d’Aujourd'hui under the heading 'Unité Residentielle'.

The outline brief offered to Goldfinger by London County Council had envisaged three 15-story 'point blocks' on the site, so the decision to combine these into a single slab block of 27 storeys was a design decision of his own. The whole concept of Balfron Tower, with an access gallery only on every three floors, would not by now be permissible under Part M of the Building Regulations (covering access) because the flats above and below the galleries do not have reception space on the same level as entry. Part L (covering energy conservation) would also make his architecture very difficult. The spatial transparency and structural articulation that is key to it have effectively been banned. The architectural rigour, however, remains compelling and the urban proposition a potentially viable option worth evaluation.

Of their potency there can be no doubt. The extreme slenderness in relation to height of the principal block of Balfron with its widely separated circulation tower accentuates their scale. To approach the main entrance from the west along the very direct path is to experience an exciting spatial sensation as one moves across the highly modelled 'green' ground plane, first alongside a ravine (the sunken service road), then across a bridge, past a ‘gatehouse’, and finally across what feels like a drawbridge under surveillance from arrays of gun-slots above, before entering the 'castle' - or tower - itself. The exposed aggregate surface of most external walls, though softened by radius corners, adds to the 'castle-like air’. From these, project gargoyles. The lift lobby is unexpectedly tall - like all those above, it is a storey-and-a-half high - and well appointed: it is lined with green marble, mostly still intact, and would have been well-lit originally when the entrance doors were plate glass - long since replaced with a heavy timber screen and door controlled by entry phone. The lift arrives promptly enough and one emerges into an upper lift lobby, equally lofty but this time with no marble and lit by an array of slit windows (the 'gun slots') in two staggered rows – vertically pivoted so that they can be opened for cleaning from inside (but evidently never are) without allowing an opening wide enough to fall out. From there another bridge leads across the vertiginous gulf between the circulation tower and the main block, with deep windows on either side, and through two pairs of swing doors (many of the original with moulded timber door handles survive), and into the access gallery.

Scarcely credible, these galleries were originally open, albeit with parapets about 1750mm high, so the quarry-tiled floor undulates slightly to create falls for drainage. Natural light streams in, lighting up the brightly-coloured tiles covering the walls opposite, punctuated by doors to three flats per structural bay, and by the kitchen windows of the two-person flats on the same level. These walls advance and recede, avoiding the oppressiveness of a corridor – very different from the blank and flat walls of the ‘streets in the air’ at Park Hill in Sheffield. Once inside the flat, the breathtaking panorama of London unfolds before you.

This was the spatial sequence I experienced every day for a week. Once inside the flat - in my case on the 24th floor - the sky dominates the view in both directions. This is as expected by the Modern Movement, but perhaps not the noise: the hope was that by building tall away from roads the noise of traffic would be lost. But the traffic approaching the Blackwall tunnel towards the south crossed by that on the East India Dock Road, right next to Balfron, is more than enough to fill the air with sound at the highest level. From the generous balcony this is noticeable and would perhaps be so within the fat with the windows open, but with them closed in October it was acceptable. Visually the sense of spatial intoxication was for me real and was heightened by the feeling that one was in touch with that space. That one could open the windows and go out onto the balcony, where pigeons could land on the planters and even squirrels run along them, and also by the shallow depth of the wide-frontage flats bringing intense light from both sides right into the centre. The drama of the changing sky was a constant source of wonder. Storms would move across and the buildings of the City visible to the west were illuminated pink by the rising sun in the morning and silhouetted dark against a pink sky in the evening.

There is no formula that is infallible, but there have been people who have managed to forge something exciting and coherent out of the theory, technology, briefs, and legislation of their time - which is what we seek to conserve. I have no doubt that Goldfinger was such a person and I felt justified after my stay at Balfron in having earlier in the year (nominated on behalf of DOCOMOMO-UK) all his work on the Brownfield Estate for listing at Grade 2* level, to match Trellick Tower, including the open spaces and incidental buildings which are critical but none of which are specifically included in the present partial Grade 2 listing. I was much helped by David Roberts who is teaching at the Bartlett and writing a PhD on the history of the occupants of Balfron. He was able to furnish many testimonials to it as a place to live – important in post-war listing nominations where 'fitness for purpose' has to be demonstrated. At his request the nomination recommends that the estate's social status be written into the listing description, like that of the Finsbury Health Centre. Grade 2 * listing would ensure the involvement of English Heritage in any assessment of whatever works are planned to Balfron post-privatisation. It did not prevent the prospective architects for the works to Balfron - Studio Egrett West - from getting consent for a drastic approach to the refurbishment of Park Hill, but Balfron is a cross-wall structure that will allow less scope for drastic alteration, and its formal qualities will, it is to be hoped, receive the recognition they merit.

To approach the main entrance from the west along the very direct path is to experience an exciting spatial sensation as one moves across the highly modelled 'green' ground plane, first alongside a ravine (the sunken service road), then across a bridge, past a ‘gatehouse’, and finally across what feels like a drawbridge under surveillance from arrays of gun-slots above, before entering the 'castle' - or tower - itself. The exposed aggregate surface of most external walls, though softened by radius corners, adds to the 'castle-like air’. From these, project gargoyles. The lift lobby is unexpectedly tall - like all those above, it is a storey-and-a-half high - and well appointed: it is lined with green marble, mostly still intact, and would have been well-lit originally when the entrance doors were plate glass - long since replaced with a heavy timber screen and door controlled by entry phone. The lift arrives promptly enough and one emerges into an upper lift lobby, equally lofty but this time with no marble and lit by an array of slit windows (the 'gun slots') in two staggered rows – vertically pivoted so that they can be opened for cleaning from inside (but evidently never are) without allowing an opening wide enough to fall out. From there another bridge leads across the vertiginous gulf between the circulation tower and the main block, with deep windows on either side, and through two pairs of swing doors (many of the original with moulded timber door handles survive), and into the access gallery.

Scarcely credible, these galleries were originally open, albeit with parapets about 1750mm high, so the quarry-tiled floor undulates slightly to create falls for drainage. Natural light streams in, lighting up the brightly-coloured tiles covering the walls opposite, punctuated by doors to three flats per structural bay, and by the kitchen windows of the two-person flats on the same level. These walls advance and recede, avoiding the oppressiveness of a corridor – very different from the blank and flat walls of the ‘streets in the air’ at Park Hill in Sheffield. Once inside the flat, the breathtaking panorama of London unfolds before you.

This was the spatial sequence I experienced every day for a week. Once inside the flat - in my case on the 24th floor - the sky dominates the view in both directions. This is as expected by the Modern Movement, but perhaps not the noise: the hope was that by building tall away from roads the noise of traffic would be lost. But the traffic approaching the Blackwall tunnel towards the south crossed by that on the East India Dock Road, right next to Balfron, is more than enough to fill the air with sound at the highest level. From the generous balcony this is noticeable and would perhaps be so within the fat with the windows open, but with them closed in October it was acceptable. Visually the sense of spatial intoxication was for me real and was heightened by the feeling that one was in touch with that space. That one could open the windows and go out onto the balcony, where pigeons could land on the planters and even squirrels run along them, and also by the shallow depth of the wide-frontage flats bringing intense light from both sides right into the centre. The drama of the changing sky was a constant source of wonder. Storms would move across and the buildings of the City visible to the west were illuminated pink by the rising sun in the morning and silhouetted dark against a pink sky in the evening.

Balfron Tower, long referred to as the 'lesser known', 'smaller' or 'earlier' version of Goldfinger's similar Trellick Tower, has this year been getting all the publicity. The most obvious reason is that the tower (27 storeys with 146 dwellings completed in 1968, the first phase of Goldfinger’s work on the LCC's Brownfield Estate in Poplar, East London is being emptied by its housing association owners Poplar HARCA for sale to private developers. While this lengthy process is going on, 40 vacated flats have been made available to the Bow Arts Trust for letting on short tenure to artists as live-work units (as well as numbers of flats to other organisations), with the result that there has been burgeoning artistic activity there over the last three years. It culminated this year in the so-called Balfron Season of events, exhibitions, happenings - even overnight performances of Macbeth -, and the involvement of the British Council, the Royal College of Art, and the National Trust. The Trust, already owners of Goldfinger's former house in Willow Road, Hampstead, were invited to open a 'pop up property’ in the flat on the top floor at the south end of the block that Erno Goldfinger with his wife Ursula famously occupied for two months in 1968 to monitor his own work for real. Indicative though all this is of interest in Goldfinger's work, it leaves unanswered some of the fundamental questions about Balfron.

In the only contemporary publication of it, in Architecture d'Aujourd'hui (Feb-March 1967), notes in its short text that the architects ‘adopted a policy of building tall (the principal building has 27 storeys) in order to leave a large part of the site free’. This must have been written by Goldfinger himself since, as the London correspondent for that magazine, he was responsible for sending all the material published about projects in Britain. The idea that space, and especially green space, was a fundamental benefit as a setting for human habitation was fundamental to the Modern Movement in architecture. It reflected the view that 'space' was a critical element in architecture and urbanism – ‘Light, Space, Greenery’ was the slogan Le Corbusier attached to his Radiant City. But it is an ideal that has been questioned, or more exactly, rejected for at least the last fifty years.