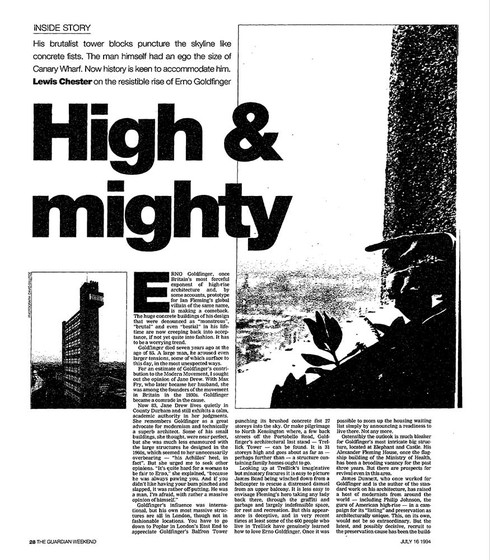

Lewis Chester, High & mighty, The Guardian Weekend, July 16 1994

Goldfinger’s influence was international but his most massive structures are all in London, though not in fashionable locations. You have to go down to Poplar in London’s East End to appreciate Goldfinger’s Balfron Tower punching its brushed concrete fist 27 storeys into the sky.

...

“Goldfinger wasn’t just larger than life,” said Sam Webb, “he was mega larger than life. The only parallel I can think of is with de Gaulle, you know, the way he became France. Well Erno became his buildings, and his buildings became Erno.” Those who had the temerity to criticise could expect no quarter. Richard Napper, who has spent most of his career as an architect in London’s East End, remembers an explosive encounter with Goldfinger in the early 1970s when they were both, in their different ways, on the up. Napper had begun work on the design for Patriot Square, a low-rise housing estate estate in Bethnal Green which is now in the process of being “listed”. Goldfinger, meantime, was trailing clouds of glory for having “lived” at the top of Balfron Tower for all of two months before making it back to the verge of Hampstead Heath. He pronounced the Balfron experience “exhilarating”.

Napper thought that Balfron was “socially disastrous” and that Goldfinger’s PR antic was pure personal grandstanding at the expense of an area that could well do without it. He volunteered this view to Goldfinger when they met at party in Highgate and spent the next two hours being bawled all round the house. Napper believes he held his own when Goldfinger occasionally paused for breath, but acknowledges that he could find absolutely no answer to the concluding roar: “Young man, you are nothing but a greenhorn. I will have you know that my finger is not the only member of my body that is golden.”

...

“They’re really lovely, aren’t they?” said Frances Clarke, director of the National Tower Blocks Network, leafing through reproductions of the original drawings for Balfron and Trellick. “You can see why councils in the 1960s were so excited to build them. Such a pity.” Clarke would remain dry-eyed if every tower block were razed to the ground. But her current campaign is focused on the more limited objective of trying to get young families housed at lower levels. Goldfinger’s towers are among her targets, but it is hard to make an impression. Tower Hamlets council says it tries - not always successfully - to rehouse young families below the sixth floor at Balfron. Kensington and Chelsea says that “in an ideal world” it would like to impose a similar restriction at Trellick, but the scarcity of public housing resources make it impossible.

Lewis Chester, High & mighty, The Guardian Weekend

Goldfinger’s influence was international but his most massive structures are all in London, though not in fashionable locations. You have to go down to Poplar in London’s East End to appreciate Goldfinger’s Balfron Tower punching its brushed concrete fist 27 storeys into the sky.

...

“Goldfinger wasn’t just larger than life,” said Sam Webb, “he was mega larger than life. The only parallel I can think of is with de Gaulle, you know, the way he became France. Well Erno became his buildings, and his buildings became Erno.” Those who had the temerity to criticise could expect no quarter. Richard Napper, who has spent most of his career as an architect in London’s East End, remembers an explosive encounter with Goldfinger in the early 1970s when they were both, in their different ways, on the up. Napper had begun work on the design for Patriot Square, a low-rise housing estate estate in Bethnal Green which is now in the process of being “listed”. Goldfinger, meantime, was trailing clouds of glory for having “lived” at the top of Balfron Tower for all of two months before making it back to the verge of Hampstead Heath. He pronounced the Balfron experience “exhilarating”.

Napper thought that Balfron was “socially disastrous” and that Goldfinger’s PR antic was pure personal grandstanding at the expense of an area that could well do without it. He volunteered this view to Goldfinger when they met at party in Highgate and spent the next two hours being bawled all round the house. Napper believes he held his own when Goldfinger occasionally paused for breath, but acknowledges that he could find absolutely no answer to the concluding roar: “Young man, you are nothing but a greenhorn. I will have you know that my finger is not the only member of my body that is golden.”

...

“They’re really lovely, aren’t they?” said Frances Clarke, director of the National Tower Blocks Network, leafing through reproductions of the original drawings for Balfron and Trellick. “You can see why councils in the 1960s were so excited to build them. Such a pity.” Clarke would remain dry-eyed if every tower block were razed to the ground. But her current campaign is focused on the more limited objective of trying to get young families housed at lower levels. Golgfinger’s towers are among her targets, but it is hard to make an impression. Tower Hamlets council says it tries - not always successfully - to rehouse young families below the sixth floor at Balfron. Kensington and Chelsea says that “in an ideal world” it would like to impose a similar restriction at Trellick, but the scarcity of public housing resources make it impossible.