p. 155

The name ‘Balfron’ was borrowed from a town just South of Glasgow, which, according to a GLC press release perpetuated the Scottish associations with the Poplar area.

pp. 157-162

At midday on 7 June 1967, a symbolic final skip of concrete was slowly hoisted to the roof of Balfron, the crane hook returning to the ground with a barrel of beer. This was the signal for the workmen to retire to the canteen for celebratory beer and sandwiches, and for the invited guests to enter the marquee for a cold buffet lunch. Ernö’s vision of social housing had at last been transformed from idea into hard fact. With the opening of the building in late February of 1968, Ernö could not prove to his critics that tall social housing was the way forward.

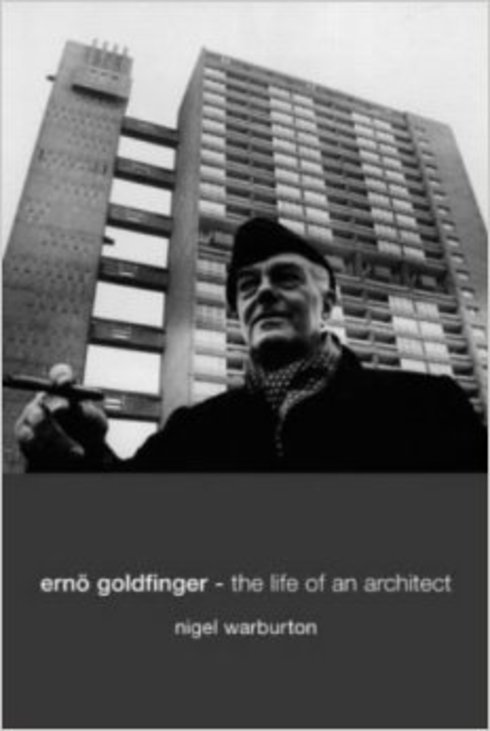

Ernö grasped the opportunity to make a public commitment to the virtues of high-rise living. The building might look foreboding from the outside but, as he hoped to demonstrate, that was completely compatible with well-planned living spaces, with stunning views across London, daylight, heating and all the prerequisites for twentieth-century city living. In what even his critics conceded was at the very least an inspired publicity stunt, he and Ursula lived for two months in flat 130 on the twenty-sixth floor from February 1968, paying the full unsubsidised rent of £11.10s (compared with the subsidised rent of £4.15s.6d that council tenants would pay for the same flat). This resulted in coverage by the national press, television and radio, almost all of it favourable. Ernö even received fanmail, so unusual was it for an architect to inhabit the building he had designed, particularly when the building was intended as social housing and built on a tight budget. Ernö, Ursula and various members of the GLC posed for photographers on their balcony overlooking the Thames; television and radio interviewers made appointments to visit. But the Goldfingers’ stay was more than just publicity and a series of photo-opportunities. It was completely consistent with his view of the art of architecture that Ernö should want to experience the enclosed space he had created form the inside. He recognised the extent to which his designs would shape people’s lives and that this brought with it responsibilities:

“Families will spend most of their lives in the flats I design. I must do everything possible to iron out problems.”

He was also keen to answer critics of high-rise living, many of whom had never tried it and so in one sense didn’t know what they were talking about. He would be able to give a far more informed opinion of the benefits and problems when he had experienced them himself. Balfron was planned as the first of many high-rises he would design, and he wanted to benefit from this opportunity to learn about what worked and what needed further thought.

…

In fact Ernö’s empiricism paid off, both as promotion for high-rise living and as experimental testing of his design. One of the more frustrating features of Balfron, and not one that could be easily remedied within that building, was that there were only two lifts.

…

For the Goldfingers there was no question of simply living in the building and observing its functioning in a non-interactive way. They had a mission to facilitate the social intermingling of the tenants, ‘my tenants’ as Goldfinger grandly referred to them, though the phrase carried with it not just an arrogance (they were after all the GLC’s tenants), but also connotations of fatherly concern. This was social housing, not just housing. Goldfinger was well aware that for this project to work effectively, the people living within it had to relate appropriately to each other:

“The success of any scheme depends on the human factor – the relationships of people to each other and the frame of their daily life which the building provides.”

The building was the shell within which these relationships evolved, though obviously its design and upkeep could facilitate or hinder their interactions.

In the case of Balfron, many of the tenants already knew each other because most of them had been rehoused street by street from the surrounding neighbourhood. Of the first 160 families housed in Balfron, only two were outside Tower Hamlets. Wherever possible, former neighbours were rehoused in flats sharing a common access gallery. The Goldfingers engaged in some gentle and well-lubricated social engineering by organising a series of parties. Floor by floor they invited the tenants up to their flat for champagne (a second fridge had to be installed to keep supplies well-chilled) and a chance to meet their neighbours as well as the the architect.

…

The Goldfingers’ genuine desire for the project to be a success, together with their approachability, were greatly appreciated. Those who met Ernö did not doubt his sincerity: ‘he was really considerate’ one declared, ‘He kept coming back after he had left to see how we were getting on.’ Ursula transcribed into her notebook how another woman expressed her enthusiasm: ‘Mrs Goldfinger you should stay longer! You are ACCEPTED! I know all the tenants and I’m telling the truth. You are ACCEPTED!’ Ursula would chat to neighbours in the lifts about their new homes or visit them, giving them the chance to point to flaws in the design of the buildings. She never heard anybody express the slightest regret about having left their old East End terraced houses, though they did have worries about the difficulty of cleaning windows, draughts, heating services not working properly, and the trumpeting noises in high winds. Many of the tenants, though, were exuberant about their new homes: ‘I wouldn’t change it for Buckingham Palace’ one declared.

Copyright Nigel Warburton

www.virtualphilosopher.com

www.philosophybites.com

www.artandallusion.com

www.socialsciencebites.com

Ernö grasped the opportunity to make a public commitment to the virtues of high-rise living. The building might look foreboding from the outside but, as he hoped to demonstrate, that was completely compatible with well-planned living spaces, with stunning views across London, daylight, heating and all the prerequisites for twentieth-century city living. In what even his critics conceded was at the very least an inspired publicity stunt, he and Ursula lived for two months in flat 130 on the twenty-sixth floor from February 1968, paying the full unsubsidised rent of £11.10s (compared with the subsidised rent of $4.15s.6d that council tenants would pay for the same flat). This resulted in coverage by the national press, television and radio, almost all of it favourable. Ernö even received fanmail, so unusual was it for an architect to inhabit the building he had designed, particularly when the building was intended as social housing and built on a tight budget. Ernö, Ursula and various members of the GLC posed for photographers on their balcony overlooking the Thames; television and radio interviewers made appointments to visit. But the Goldfinger’s stay was more than just publicity and a series of photo-opportunities. It was completely consistent with his view of the art of architecture that Ernö should want to experience the enclosed space he had created form the inside. He recognised the extent to which his designs would shape people’s lives and that this brought with it responsibilities:

“Families will spend most of their lives in the flats I design. I must do everything possible to iron out problems.”

He was also keen to answer critics of high-rise living, many of whom had never tried it and so in one sense didn’t know what they were talking about. He would be able to give a far more informed opinion of the benefits and problems when he had experienced them himself. Balfron was planned as the first of many high-rises he would design, and he wanted to benefit from this opportunity to learn about what worked and what needed further thought.

…

In fact Ernö’s empiricism paid off, both as promotion for high-rise living and as experimental testing of his design. One of the more frustrating features of Balfron, and not one that could be easily remedied within that building, was that there were only two lifts.

…

For the Goldfingers there was no question of simply living in the building and observing its functioning in a non-interactive way. They had a mission to facilitate the social intermingling of the tenants, ‘my tenants’ as Goldfinger grandly referred to them, though the phrase carried with it not just an arrogance (they were after all the GLC’s tenants), but also connotations of fatherly concern. This was social housing, not just housing. Goldfinger was well aware that for this project to work effectively, the people living within it had to relate appropriately to each other:

“The success of any scheme depends on the human factor – the relationships of people to each other and the frame of their daily life which the building provides.”

The building was the shell within which these relationships evolved, though obviously its design and upkeep could facilitate or hinder their interactions.

In the case of Balfron, many of the tenants already knew each other because most of them had been rehoused street by street from the surrounding neighbourhood. Of the first 160 families housed in Balfron, only two were outside Tower Hamlets. Wherever possible, former neighbours were rehoused in flats sharing a common access gallery. The Goldfingers engaged in some gentle and well-lubricated social engineering by organising a series of parties. Floor by floor they invited the tenants up to their flat for champagne (a second fridge had to be installed to keep supplies well-chilled) and a chance to meet their neighbours as well as the the architect.

…

The Goldfingers’ genuine desire for the project to be a success, together with their approachability, were greatly appreciated. Those who met Ernö did not doubt his sincerity: ‘he was really considerate’ one declared, ‘He kept coming back after he had left to see how we were getting on.’ Ursula transcribed into her notebook how another woman expressed her enthusiasm: ‘Mrs Goldfinger you should stay longer! You are ACCEPTED! I know all the tenants and I’m telling the truth. You are ACCEPTED!’ Ursula would chat to neighbours in the lifts about their new homes or visit them, giving them the chance to point to flaws in the design of the buildings. She never heard anybody express the slightest regret about having left their old East End terraced houses, though they did have worries about the difficulty of cleaning windows, draughts, heating services not working properly, and the trumpeting noises in high winds. Many of the tenants, though, were exuberant about their new homes: ‘I wouldn’t change it for Buckingham Palace’ one declared.

Copyright Nigel Warburton

www.virtualphilosopher.com

www.philosophybites.com

www.artandallusion.com

www.socialsciencebites.com

In the case of Balfron, many of the tenants already knew each other because most of them had been rehoused street by street from the surrounding neighbourhood. Of the first 160 families housed in Balfron, only two were outside Tower Hamlets. Wherever possible, former neighbours were rehoused in flats sharing a common access gallery.

Copyright Nigel Warburton

www.virtualphilosopher.com

www.philosophybites.com

www.artandallusion.com

www.socialsciencebites.com

Ursula would chat to neighbours in the lifts about their new homes or visit them, giving them the chance to point to flaws in the design of the buildings. She never heard anybody express the slightest regret about having left their old East End terraced houses, though they did have worries about the difficulty of cleaning windows, draughts, heating services not working properly, and the trumpeting noises in high winds. Many of the tenants, though, were exuberant about their new homes: ‘I wouldn’t change it for Buckingham Palace’ one declared.

Copyright Nigel Warburton

www.virtualphilosopher.com

www.philosophybites.com

www.artandallusion.com

www.socialsciencebites.com