I have included excerpts below but encourage you to visit the website to see the full article.

Alice Rawsthorn, Child's Play, New York Times, November 7, 2009

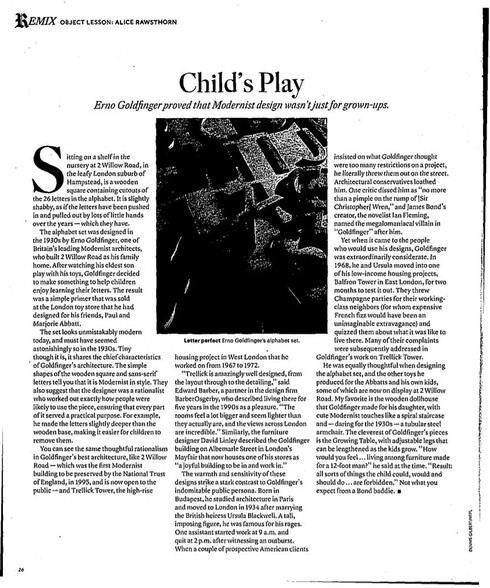

Sitting on a shelf in the nursery at 2 Willow Road, in the leafy London suburb of Hampstead, is a wooden square containing cutouts of the 26 letters in the alphabet. It is slightly shabby, as if the letters have been pushed in and pulled out by lots of little hands over the years — which they have.

The alphabet set was designed in the 1930s by Erno Goldfinger, one of Britain’s leading Modernist architects, who built 2 Willow Road as his family home. After watching his eldest son play with his toys, Goldfinger decided to make something to help children enjoy learning their letters. The result was a simple primer that was sold at the London toy store that he had designed for his friends, Paul and Marjorie Abbatt.

The set looks unmistakably modern today, and must have seemed astonishingly so in the 1930s. Tiny though it is, it shares the chief characteristics of Goldfinger’s architecture. The simple shapes of the wooden square and sans-serif letters tell you that it is Modernist in style. They also suggest that the designer was a rationalist who worked out exactly how people were likely to use the piece, ensuring that every part of it served a practical purpose. For example, he made the letters slightly deeper than the wooden base, making it easier for children to remove them.

You can see the same thoughtful rationalism in Goldfinger’s best architecture, like 2 Willow Road — which was the first Modernist building to be preserved by the National Trust of England, in 1995, and is now open to the public — and Trellick Tower, the high-rise housing project in West London that he worked on from 1967 to 1972.

“Trellick is amazingly well designed, from the layout through to the detailing,” said Edward Barber, a partner in the design firm BarberOsgerby, who described living there for five years in the 1990s as a pleasure. “The rooms feel a lot bigger and seem lighter than they actually are, and the views across London are incredible.” Similarly, the furniture designer David Linley described the Goldfinger building on Albemarle Street in London’s Mayfair that now houses one of his stores as “a joyful building to be in and work in.”

The warmth and sensitivity of these designs strike a stark contrast to Goldfinger’s indomitable public persona. Born in Budapest, he studied architecture in Paris and moved to London in 1934 after marrying the British heiress Ursula Blackwell. A tall, imposing figure, he was famous for his rages. One assistant started work at 9 a.m. and quit at 2 p.m. after witnessing an outburst. When a couple of prospective American clients insisted on what Goldfinger thought were too many restrictions on a project, he literally threw them out on the street. Architectural conservatives loathed him. One critic dissed him as “no more than a pimple on the rump of [Sir Christopher] Wren,” and James Bond’s creator, the novelist Ian Fleming, named the megalomaniacal villain in “Goldfinger” after him.

Yet when it came to the people who would use his designs, Goldfinger was extraordinarily considerate. In 1968, he and Ursula moved into one of his low-income housing projects, Balfron Tower in East London, for two months to test it out. They threw Champagne parties for their working-class neighbors (for whom expensive French fizz would have been an unimaginable extravagance) and quizzed them about what it was like to live there. Many of their complaints were subsequently addressed in Goldfinger’s work on Trellick Tower.

He was equally thoughtful when designing the alphabet set, and the other toys he produced for the Abbatts and his own kids, some of which are now on display at 2 Willow Road. My favorite is the wooden dollhouse that Goldfinger made for his daughter, with cute Modernist touches like a spiral staircase and — daring for the 1930s — a tubular steel armchair. The cleverest of Goldfinger’s pieces is the Growing Table, with adjustable legs that can be lengthened as the kids grow. “How would you feel . . . living among furniture made for a 12-foot man?” he said at the time. “Result: all sorts of things the child could, would and should do . . . are forbidden.” Not what you expect from a Bond baddie.