I have included excerpts below but encourage you to visit the websites to see the full articles, accompanying images and comments.

Benjamin Mortimer, How the Balfron Tower tenants were ‘decanted’ and lost their homes, East End Review

Last month’s announcement that the Grade II-listed Balfron Tower in Poplar will no longer contain any social housing but will instead be sold as luxury flats put an end to speculation about its future that has been going on since 2010. But questions remain about its recent past, particularly around how more than 120 family-sized East London flats have passed from the social to the private sector without anyone being evicted.

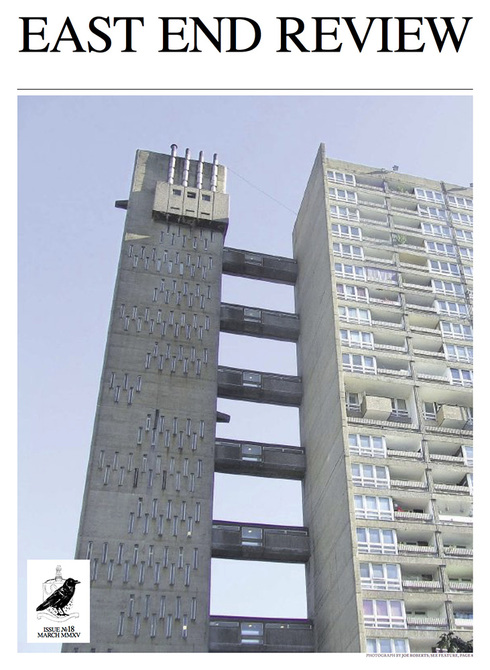

For all that it is a gigantic and imposing concrete structure, Balfron is also delicate, with spindly, human-scale walkways connecting the service tower and main building. Six flats broad and one flat thick, it is endearingly awkward-looking; broad and slim, tall and squat, rough and rectilinear all at once. All bedrooms are on the eastern face, placed for the sunrise, with balconies to the west for its setting. Designed in the brutalist mood by British-Hungarian architect Ernő Goldfinger in the late 60s, it is touched by many such small elements of genius. The view is of London, from the Thames Estuary to Hampstead Heath.

For the better part of five years, Poplar HARCA, the housing association which owns the block, has maintained that the people who used to live there – social tenants who were “decanted” to allow refurbishment work to be carried out – might in theory be permitted to move back in. It stated several times that they “possibly but not probably” had a “right of return”.

This “right” wasn’t about law but about money: whether Poplar HARCA could afford to have any social housing in Balfron Tower. Until recently it was still unsure. In an interview conducted in January, Paul Augarde, head of Creativity and Innovation at Poplar HARCA, insisted he still did not know whether or not the budget for the Balfron project would have space for some social tenants to move back in. “It’s never great,” he said of what was then the possible total sale. “You don’t want to sell stuff.”

Poplar HARCA has a lot going for it. It owns and manages 6,000 social rent homes in Poplar and has built over 1,000 homes (social and private) in the last 15 years. It has refurbished all its social lets. It helps jobless residents into work, supports social enterprises in the area and even employs its own small police force. It persuaded Barclays to open the first non-charging cash point in the whole of Poplar and caused a bridge to be built over the four-lane East India Dock Road to connect estates together. It is making physical improvements to the area of a different magnitude to anything the council ever did.

Which goes some way to explaining why residents of the Brownfield Estate, of which Balfron and its neighbour Carradale House are part, voted for ownership and management of their homes to be transferred to Poplar HARCA from Tower Hamlets Council in 2007. But what has happened at Balfron is very different to what they actually voted for.

In 2006, residents were sent a booklet about transferring to Poplar HARCA, two pages of which were of special relevance to Balfron and Carradale. Poplar HARCA would be contractually obliged to refurbish substantially both blocks, and two options for their tenants were proposed: they could remain living in their flats while the refurbishment was carried out, or they could move, as priority tenants, into new homes Poplar HARCA would build elsewhere on the Brownfield Estate. If they took the second option, their current flat would be sold privately to help pay for the project.

Poplar HARCA anticipated around 130 tenants from across both blocks would choose to leave in this first instance. Balfron had suffered from an historic lack of maintenance and anti-social behaviour was a serious problem. Many tenants took Poplar HARCA up on its offer; but many others opted to stay.

In other words, the sale of some flats in Balfron was always on the cards, but so was the prospect of social tenants continuing to live there indefinitely. This initial proposal, on which tenants voted, made no mention of a “decant”, permanent or temporary, nor indeed of any need to leave Balfron at all.

How did we get from this state of affairs to last month’s announcement that the whole of Balfron, now empty of tenants, is to be sold privately?

Crash

Poplar HARCA blames two things: the 2008 financial crisis and the refusal of planning permission for a “linked” proposal for several separate developments it submitted to Tower Hamlets Council. Approval of this proposal would have given it a solid financial resource and lowered its reliance on the sale of unwanted Balfron and Carradale flats to fund the refurbishment and other projects. Forced to apply for new developments site by site, and sell homes at post-crash prices, these flats became one of its few solid sources of money.

Since these events occurred, tenants have been “decanted” and the uncertainty of their “possible but not probable” return promulgated. If – from 2008 onwards – Poplar HARCA strongly suspected it would need to sell Balfron, why didn’t it just make a clean breast of it?

Paul Augarde argues it was simply communicating the truth of the situation, which was that Poplar HARCA did not know what was going to happen. “We were very straight,” he says. “If we’d given an absolute answer” to residents’ questions on returning, he says, “it would have been no. It would have been easier to say no.”

Decant

Poplar HARCA did not attribute the need to remove tenants in 2010 to the need to sell Balfron, instead citing a report which detailed safety risks to their remaining while work was carried out. It decided on this basis to “decant” all tenants. This makes sense – quite how people could remain in flats while their bathrooms and kitchens were renovated has never entirely been made clear. But the “decant” also meant that the sale of homes would from then on always be connected to the prospect of tenants moving back in, not to their being moved out. The question of the sale of homes would be framed around a “right of return”, not a “right to stay”.

This was the manner in which the issue was presented to tenants, who were briefed by Poplar HARCA at the end of September 2010 on the need to leave their homes. The briefing could have been clearer: “Up until reading about the process of decanting I thought we were going to temporary housing and then return,” says Michael Newman, a tenant of Balfron for many years. Printed communications, however, boded ill: “The document that I looked at was on the process of decanting, and it made no statement that I could find on returning.”

The omission caused such alarm that by October it was the subject of an FAQ on a fact-sheet distributed by Poplar HARCA. “Can I move back in when the works are complete?” was “one of the questions we just don’t know the answer to yet”, the sheet stated, before raising the prospect of selling more Balfron flats than originally intended: “We have had to re-think how we pay for the works.”

In November 2010, Newman wrote an eloquent and moving letter to Andrea Baker, Director of Housing at Poplar HARCA, asking if there had been a misunderstanding: “[I] see my flat, my home, as a safe haven with memories of my brothers, and an inspirational, poetic view that has helped me through very difficult times,” he wrote. “I have lived for the past few weeks with the worry of losing my home.

“I am writing to ask you to reassure me about my home and our community.” Baker wrote back the very next day. But she was unable to offer anything further by way of reassurance than the “possibly but not probably have a right of return” formulation.

“Right of return”, not “right to stay”

From 2010, Poplar HARCA worked with residents on relocating. Building work was (and still is) yet to start. As years went by, the realistic option for waiting residents was to cease to pursue even a moral “right of return”.

“I have been treated very well by HARCA in the decant and do feel gratitude for how they supported the move,” says Michael Newman now. He has resettled in Carradale House. “I am now happy where I live. I can see my old flat from the balcony of my new one, and I am starting a new life.”

So is Balfron Tower. Now that all tenants have been re-housed, physically and psychologically, Poplar HARCA has finally applied for planning permission for the refurbishment and has formed a partnership with developer London Newcastle to sell the flats.

What comes of all this? It’s astonishing that a social landlord started with the plan of refurbishing a listed building for its social tenants and found that it was able to do so only if it sold the building into private hands – while still being contractually obliged to carry out the work. Other housing associations may well be put off by this from pursuing such ambitious projects, and it is a shame, to say the very least, that Poplar HARCA, for all its achievements, could not set them a better example.

Balfron Tower set for refurbishment, Docklands News

The Ernö Goldfinger-designed Grade II-listed Balfron Tower in Poplar is to be refurbished by a consortium led by property developer Londonewcastle. A planning application for the 1960s Brutalist masterpiece, sister to the Trellick Tower in north Kensington will be submitted by May, with a decision expected by September.

Mike Brooke, East End tenants ‘booted out’ of Goldfinger’s iconic Balfron Tower’ claim, East London Advertiser

Campaigners have protested against a social housing organisation in London’s East End they claim is booting out low-income tenants from Erno Goldfinger’s iconic 1960s Balfron Tower.

Members of Tower Hamlets Renters and Action East End demonstrated outside the offices of Poplar Harca Housing’s offices yesterday over a planning application they fear would “evict social tenants” from the ex-council block which is due to be refurbished after 46 years.

Around £20 million is needed to spruce up the high-riser in East India Dock Road, overlooking the Blackwall Tunnel entrance, before most of its 146 rented flats are “sold off to bankers and investors” with no chance for the tenants to return, protesters believe.

“People bang on about the architectural importance of Balfron Tower,” campaigner Glenn McMahon said. “But frankly, its legacy will be more ‘ironic’ than ‘iconic’.

“Goldfinger designed it for the East End’s working classes—yet Poplar Harca has kicked them out and is selling their homes to bankers and investors.”

The 26-storey tower opened in 1968 brings in around £1.5m a year in rents, which campaigners say is enough to pay the refurbishment loan over 20 years.

“The wholesale transfer of low-income tenants in favour of people who can afford mortgages up to £1m is ‘social cleansing’ by any standards,” McMahon added.

But Poplar Harca today denied trying to get rid of the tenants. It had moved out families into larger homes in the neighbouring Carradale House who had been stuck in overcrowded accommodation.

A spokesman said: “We’ve built 1,000 social homes in the area over the last 15 years and are refurbishing all tenant accommodation to ‘Decent Homes’ standard. Contracts are also in place to build another 300 homes in the Poplar and Bow area, many of them family homes for local need.”

The agreement with Tower Hamlets Council when Poplar Harca took over Balfron Tower in 2007 specified that it had to be renovated.

Tenants were told before the hand-over that homes “would need to be sold” to pay for the architectural Grade II-listed restoration.

They voted at the time for Poplar Harca to run the block.

Londonewcastle goes for gold in east London, Hannah Brenton

There are not many property developers with an early 1978 Damian Hirst print on nuclear warfare in their office entrance hall.

Or that would hold an interview in their own basement bar, equipped with stripped-back lighting and an extensive booze collection. But for Londonewcastle, a developer trying to tap into London’s up-and-coming creative classes, perhaps it’s fitting.

Their latest project, the redevelopment of 1960s monument Balfron Tower, will turn a tired social housing scheme into contemporary flats in the still relatively unloved area of Poplar, east London.

“We feel it’s a piece of modern brutalism that will hopefully be referred back to as to how an iconic building like this, which is dilapidated and deteriorating quite badly, should be moved forward into the future,”

Londonewcastle chief operating officer Robert Soning said in an exclusive interview with Property Week.

“We’re massive fans of Goldfinger — we love what he tried to achieve, which are effectively communities in the sky. We felt that from an architectural point of view that era [the 1960s] was a concrete disaster — but out of this grew some real gems.”

The project came about at the end of 2014 when a joint venture was created to redevelop the Ernö Goldfinger-designed Grade-II listed brutalist icon, with Poplar Housing and Regeneration Community Association (Harca), United House Developments and Londonewcastle teaming up to form Balfron Tower Developments.

It sounds like a no-brainer. But the refurbishment of the tower, the sister to the Trellick tower in north Kensington, is not without its controversy. As existing social housing, it will be redeveloped into private flats - with all the pain of dislocation this will entail for some residents. But, Soning argues, it is a “perfect example” of regeneration at work as the money is to be ploughed back into housing association Poplar Harca’s coffers.

“It has to do this to finance its wider programme, which is hugely beneficial to Poplar as an area and I admire [Poplar Harca] for its ambition and vision,” he elaborates. “I don’t think anyone can put a valid argument up as to why it should not be doing this. It makes total sense.”

The joint venture will now take its proposals, which will require careful work as barely any structural changes to the building are permitted, to the local community, English Heritage and through the planning process. It hopes to submit a planning application in May 2015 and gain approval by September 2015.

Fighting talk

For Londonewcastle, the project is certainly eye-catching and it adds to the redirection of the company. The developer, set up by Soning and chief executive David Barnett in 1995, had a tough time navigating the recession, undertaking a corporate restructuring with HBOS in 2006 and again with Lloyds in 2010.

“Unfortunately we came of age in a very, very tough period of time — which has probably been the making of the business,” says Soning. “I have no regrets. When the party was in full swing we had grand offices, with 50 people working for me. I used to walk in there in the morning and think how did this happen, I really did. It was a life lesson for us and I believe it’s the reason why we’ve become successful today.”

Cutting its cloth to adapt to a changed landscape, the company restructured, came out of Lloyds ownership and formed a new partnership with UK & European Investments, the Lewis Family Trust. It also set the business on a new four-pronged approach involving: smaller, niche London sites; a development management business; council frameworks such as Westminster’s Developer Framework (with Bouygues Development); as well as its own pipeline.

“The business has diversified: it’s our own portfolio we’re working on and the development management of other schemes for other organisations as well. We’re quite proud of the fact that we’ve managed to have the vision to do that,” Soning says.

On the development management side, Londonewcastle has secured planning for the redevelopment of the Hurlingham Retail Park in Fulham with Royal London Asset Management and is bringing forward plans for a key site within the Whitechapel Vision Masterplan.

For its own pipeline, as well as the partnership at Balfron, it is involved in a joint venture with Bouygues Development in Queen’s Park, Kelaty House — a mixed-use development in Wembley — and the redevelopment of the Huntingdon Estate in Shoreditch.

“If we developed everything we were involved in, there’s a gross development value of £1.25bn so it’s quite a big business now,” claims Soning.

In a bid to streamline the business, Londonewcastle has also been selling out of certain schemes. Property Week revealed in November that housebuilder Redrow had bought 500 Chiswick High Street for more than £20m from Londonewcastle. Soning says schemes the developer does not feel suit its brand — which is aimed squarely at the upper end of the mid-market at £750-£1,500/sq ft — will be sold off once it has won planning consent for them.

The design-led developer is also considering its options at its Wembley scheme, where it has consent for 500,000 sq ft of student accommodation. Soning says the company could “develop it, JV it, sell it off, or just sit with it”, adding that Wembley is becoming one of London’s regeneration success stories under Quintain’s watch, alongside Argent’s efforts at King’s Cross.

Rising in the east

Londonewcastle’s focus has gravitated towards east London in recent years, which Soning notes is still benefiting from the transport links put in place in the run-up to the Olympics. Indeed, he adds, the up-and-coming areas in the east are more exciting to him than the already established locations in the heart of the city.

“It’s an evolution and I look forward to that evolution and I want to be part of it. It’s difficult for us to operate in prime central London. We’ve learnt too much over the years to fall into that trap,” he adds.

“At the moment, we’re very much focusing on zone 2 and zone 3. We believe that’s very much where the sweet spot of the market is. I actually believe there is potentially an oversupply of residential in zone 1 and parts of zone 2 within the next five years.”

There is also a risk overseas investors will get “fed up” with the increasingly high pricing in the two central zones, he argues, impacting schemes and developers over-reliant on such sales. Instead, he points to the likes of Plaistow, Peckham, Deptford, Hackney Downs, London Fields, Walthamstow and Stratford as areas where the workforce of London is going to want to live.

However, the London housing market is facing a period of stagnation and uncertainty rather than a full-on fall in prices, believes Soning. He lays the blame for price drops at the end of last year on price hikes in the summer causing a “fake bubble”. “Everyone’s under the illusion it’s dropped; it hasn’t. It was just in a false bubble. It’s the market’s fault it happened. They created that monster,” he argues.

With the recession firmly behind it, Londonewcastle seems equipped to weather any slowdown in the market. Aggressively on the acquisitions trail again, the developer will undoubtedly get involved in more Balfron-esque schemes in the year to come.

James Walsh, Balfron Tower - Not for the likes of us, Morning Star

Originally built for London’s working class, Balfron Tower in east London has been cleared of its social tenants and is being refurbished and sold off as private flats more befitting its ‘iconic’ status, writes James Walsh

The ugliness of a building is a subjective assessment, and one that tends to change as certain styles go in and out of fashion. However, we can talk of the ugliness of a building’s purpose.

Take London’s Shard. Owned by the Qatari government, which has just added Canary Wharf to its property portfolio, it serves as a plaything of the super-rich, with luxury hotel and restaurant and as-yet-unsold penthouse apartments.

In the context of a severe housing crisis, this grotesque building takes on a dystopian air. The tower lurks over the city’s skyline, a constant reminder of current economic realities.

There is a glut of new towers going up around London, most of which are as socially unnecessary as the Shard. London Mayor Boris Johnson has been happy to waive the most derisory of affordable housing requirements for major projects on “viability” grounds. Developers are able to plead “commercial sensitivity” to justify their questionable figures. “Fully private block with no social housing,” boasted one new development in Greenwich to potential “off-plan” investors.

The conversion of Tottenham Court Road’s Centrepoint tower into flats for the rich may feel ironic to those who remember it becoming a focus point of protest against homelessness as far back as 1974.

The fate of the brutalist Balfron Tower, built in Poplar, east London in the late ’60s to a design by the famed architect Erno Goldfinger, seems just as insulting as the Shard’s rise. This Grade II-listed tower is a reminder that London’s most high-profile building projects were once for a very different purpose — to house its working-class citizens.

Balfron has been cleared of social tenants — “decanted,” in the language of the day — and is being refurbished and sold off as private flats more befitting its “iconic” status. It has become synonymous with the idea that certain types of property — and certain types of view — are not good enough for normal people.

The building also tells us a lot about the narrative of social housing in recent years. After years of neglect and underinvestment by a cash-strapped Tower Hamlets Council, ownership of the tower was transferred, along with other local estates, to housing association Poplar HARCA, in 2007.

Residents were promised new kitchens and bathrooms, alongside new entry systems and greater investment for the area, and voted in favour of the transfer.

Poplar HARCA initially claimed that residents in the Balfron would be able to move back in after refurbishment, but eventually admitted that the whole block would need to be sold off to private developers.

The block’s sale will “serve a catalyst to revitalise the local community,” according to Rick de Blaby, the chief executive of United House Developments, whose website claims the tower will be refurbished “in a manner that is in keeping with Goldfinger’s original vision for the space.”

Fellow redevelopers “luxury residential property” company LondonNewcastle prefer to concentrate on the tower’s “edgy” appeal, pointing out that it has appeared in a gritty music video for Oasis and Danny Boyle’s apocalyptic zombie thriller 28 Days Later.

The tower’s proximity to Canary Wharf will prove popular with architecturally savvy financiers and buy-to-let speculators.

Those who once lived there are less happy.

“It has become an icon for privatisation,” says former resident Michael Newman.

“For the most beautiful building with an incredible potential to develop and sustain a vibrant community, to be sold off to the rich, and this to be celebrated in the architectural press — this is the sign of our times.”

Also symptomatic is who has been living in the block as it awaits its new rich owners. Alongside property guardians happy to give up tenancy security for cheap rents, the Bow Arts Trust brought in artists as residents to “celebrate” those who once lived there, provided the work remained vague enough not to feature the plight of the departing tenants.

This move backfired, with Oliver Wainwright summing up the process in the Guardian as a “live gentrification jamboree.” Not the coverage the developers would have been hoping for.

In fact, the wider background to this privatisation party has been one of local people fighting back. The New Era estate in Hackney, east London, became a focal point in the fight against gentrification. Protest and campaigning led to a humiliating climbdown by the US asset management firm Westbrook.

Many have been inspired by the work of the Focus E15 mothers, whose occupation of the Carpenters Estate brought stark attention to post-Olympics attempts at social cleansing in Newham. Focus E15 mothers will be among those leading today’s March for Homes, when people will march on City Hall to demand affordable rents, a new building program and an end to the sell-off and demolition of social housing.

“We are not marching for the electoral politicians,” said Focus E15 spokeswoman Saskia O’Hara. “We are marching to inspire people to take up the fight for housing.”

One former Balfron leaseholder, Vanessa Crawford, is encouraged by the new wave of activism and only wishes it had happened sooner “so that a campaign could have started while tenants were resident.

“The insidious creep to total privatisation over more than four years has precluded this.”

While it may be too late to save Balfron Tower from its fate, it must not be allowed to become a monument to a past era. We must all keep on campaigning, organising and protesting to ensure that future Londoners can look up and see a skyline that does not exclude them.

Today’s march would be a good place to start.

Ruby Stockham, The latest protest against eviction in London is a depressing reminder of the government’s priorities, Left Foot Forward

This week, a group of activists are occupying an empty house on the Sweets Way estate in Barnet. Many of the activists are tenants, or former tenants, of the estate, and are facing eviction due to Annington Homes’ redevelopment plans.

Annington Homes plan to get rid of over 150 homes and replace them with 288 ‘units’. They have committed to just 11 per cent affordable homes in the new development.

Those who have already been forced out are scattered across London in temporary accommodation, and so the occupation is also chance to catch up with the community which they have been a part of for five years.

The plans for Sweets Way are just the latest in a series of hugely unfair redevelopment projects that have taken place in London over the last year.

Taking part in the Sweets Way protest is Jasmin Stone, one of the young mothers who made headlines last year when she led the Focus E15 campaign, which fought to allow residents of the Carpenters estate in Newham to be rehoused locally.

In December, residents staged a protest at plans to sell off the New Era estate in Haggerston to an American company with ties to Richard Blakeway, Boris Johnson’s deputy.

Rents were to be almost doubled – reaching £2,000 for a two bedroom flat – and residents said it amounted to social cleansing. Eventually the development was sold to Dolphin Square Charitable Foundation, who committed to delivering low cost rents, although the current tenants are unlikely to be able to stay there for more than a couple of years.

One of the most troubling cases of so-called social cleansing in recent months is that of Balfron Tower in Poplar, which is due to be refurbished after 46 years. Designed by the modernist architect Erno Goldfinger for social tenants, the building has become iconic and thus ripe for redesign.

Tenants were told before the hand-over that homes ‘would need to be sold’ to pay for the architectural Grade II-listed restoration. As they battled their eviction, a series of pop-up events were hosted in the building: supper clubs, art exhibitions and all night theatre performances.

One artist planned to drop a piano off the roof, in what she called an exploration of sound, and others called an act of extraordinary class contempt, as residents panicked about where and how they were going to live now. It was gentrification taken to its logical extreme and acted out, unwittingly, as art.

A certain amount of gentrification is inevitable, and it can bring good things. But more and more often it seems to be being implemented in London with an inexcusable cruelty and lack of planning. Newham Council considered rehousing the E15 mothers in Manchester, Birmingham and Hastings. Away from all their families and friends, how would these women be expected to work and take care of their children?

Businesses are suffering too, as loyal customer bases are forced out and expensive new shops compete for the new residents. Several long-standing music venues have been forced to close after residents moved into areas which they knew were nightlife hubs, costing organisers their livelihoods.

London needs better council housing, and more of it. Instead, the Conservatives have presided over the lowest level of social housing building for decades, and backed redevelopment plans which break up communities and leave people at risk of extreme poverty. Boris Johnson’s strategy of favouring overseas investors is contributing to the huge social housing shortfall, and bizarrely trying to answer a housing crisis by building homes people can’t afford.

There are other options: Community Housing Associations, cooperative housing and Community Land Trusts all offer ways to make housing affordable long-term. This and any future government need to rethink their calculation of value – affordable houses hugely benefit local communities and businesses, and stop people being so dependent on welfare. It is about looking further into the future, and imagining what estates, and the people who live in them, could be doing in 10 or 20 years time.

Natalie Bloomer, The fight to stop London becoming a city for the rich, Politics.co.uk

Gentrification, social cleansing and regeneration are all terms that have been used to describe what is happening to many housing estates across London. But whatever you call it, the result is the same: working class and lower income families being pushed out of the capital.

…

In the run up to the general election, much has been said about the number of homes that need to be built to tackle the housing crisis. But there is little trust among many of the campaigners on the issue.

The Balfron Social Club was set up after tenants of the iconic Balfron Tower in Poplar were moved out to allow the building to be transformed into luxury flats. The campaign is calling for at least 50% of the new flats to be socially rented. A member of the group says:

"Following the general election and the subsequent Tower Hamlets mayoral election, we intend to increase pressure on elected politicians to not just make statements about the dismantlement of social housing but to actively get involved in ensuring it's terminated."

Social media has allowed many of the campaigns to link up and support each other and barely a week passes without a message on Twitter calling for fellow activists to attend a protest somewhere in London.

…

Londonewcastle goes for gold in east London, Hannah Brenton

“We feel it’s a piece of modern brutalism that will hopefully be referred back to as to how an iconic building like this, which is dilapidated and deteriorating quite badly, should be moved forward into the future,”

Londonewcastle chief operating officer Robert Soning said in an exclusive interview with Property Week.

“We’re massive fans of Goldfinger — we love what he tried to achieve, which are effectively communities in the sky. We felt that from an architectural point of view that era [the 1960s] was a concrete disaster — but out of this grew some real gems.”

Benjamin Mortimer, How the Balfron Tower tenants were ‘decanted’ and lost their homes, East End Review

Last month’s announcement that the Grade II-listed Balfron Tower in Poplar will no longer contain any social housing but will instead be sold as luxury flats put an end to speculation about its future that has been going on since 2010. But questions remain about its recent past, particularly around how more than 120 family-sized East London flats have passed from the social to the private sector without anyone being evicted.

For the better part of five years, Poplar HARCA, the housing association which owns the block, has maintained that the people who used to live there – social tenants who were “decanted” to allow refurbishment work to be carried out – might in theory be permitted to move back in. It stated several times that they “possibly but not probably” had a “right of return”.

This “right” wasn’t about law but about money: whether Poplar HARCA could afford to have any social housing in Balfron Tower. Until recently it was still unsure. In an interview conducted in January, Paul Augarde, head of Creativity and Innovation at Poplar HARCA, insisted he still did not know whether or not the budget for the Balfron project would have space for some social tenants to move back in. “It’s never great,” he said of what was then the possible total sale. “You don’t want to sell stuff.”

In 2006, residents were sent a booklet about transferring to Poplar HARCA, two pages of which were of special relevance to Balfron and Carradale. Poplar HARCA would be contractually obliged to refurbish substantially both blocks, and two options for their tenants were proposed: they could remain living in their flats while the refurbishment was carried out, or they could move, as priority tenants, into new homes Poplar HARCA would build elsewhere on the Brownfield Estate. If they took the second option, their current flat would be sold privately to help pay for the project.

Poplar HARCA anticipated around 130 tenants from across both blocks would choose to leave in this first instance. Balfron had suffered from an historic lack of maintenance and anti-social behaviour was a serious problem. Many tenants took Poplar HARCA up on its offer; but many others opted to stay.

In other words, the sale of some flats in Balfron was always on the cards, but so was the prospect of social tenants continuing to live there indefinitely. This initial proposal, on which tenants voted, made no mention of a “decant”, permanent or temporary, nor indeed of any need to leave Balfron at all.

Poplar HARCA blames two things: the 2008 financial crisis and the refusal of planning permission for a “linked” proposal for several separate developments it submitted to Tower Hamlets Council. Approval of this proposal would have given it a solid financial resource and lowered its reliance on the sale of unwanted Balfron and Carradale flats to fund the refurbishment and other projects. Forced to apply for new developments site by site, and sell homes at post-crash prices, these flats became one of its few solid sources of money.

Since these events occurred, tenants have been “decanted” and the uncertainty of their “possible but not probable” return promulgated. If – from 2008 onwards – Poplar HARCA strongly suspected it would need to sell Balfron, why didn’t it just make a clean breast of it?

Paul Augarde argues it was simply communicating the truth of the situation, which was that Poplar HARCA did not know what was going to happen. “We were very straight,” he says. “If we’d given an absolute answer” to residents’ questions on returning, he says, “it would have been no. It would have been easier to say no.”

Poplar HARCA did not attribute the need to remove tenants in 2010 to the need to sell Balfron, instead citing a report which detailed safety risks to their remaining while work was carried out. It decided on this basis to “decant” all tenants. This makes sense – quite how people could remain in flats while their bathrooms and kitchens were renovated has never entirely been made clear. But the “decant” also meant that the sale of homes would from then on always be connected to the prospect of tenants moving back in, not to their being moved out. The question of the sale of homes would be framed around a “right of return”, not a “right to stay”.

This was the manner in which the issue was presented to tenants, who were briefed by Poplar HARCA at the end of September 2010 on the need to leave their homes. The briefing could have been clearer: “Up until reading about the process of decanting I thought we were going to temporary housing and then return,” says Michael Newman, a tenant of Balfron for many years. Printed communications, however, boded ill: “The document that I looked at was on the process of decanting, and it made no statement that I could find on returning.”

The omission caused such alarm that by October it was the subject of an FAQ on a fact-sheet distributed by Poplar HARCA. “Can I move back in when the works are complete?” was “one of the questions we just don’t know the answer to yet”, the sheet stated, before raising the prospect of selling more Balfron flats than originally intended: “We have had to re-think how we pay for the works.”

In November 2010, Newman wrote an eloquent and moving letter to Andrea Baker, Director of Housing at Poplar HARCA, asking if there had been a misunderstanding: “[I] see my flat, my home, as a safe haven with memories of my brothers, and an inspirational, poetic view that has helped me through very difficult times,” he wrote. “I have lived for the past few weeks with the worry of losing my home.

“I am writing to ask you to reassure me about my home and our community.” Baker wrote back the very next day. But she was unable to offer anything further by way of reassurance than the “possibly but not probably have a right of return” formulation.

From 2010, Poplar HARCA worked with residents on relocating. Building work was (and still is) yet to start. As years went by, the realistic option for waiting residents was to cease to pursue even a moral “right of return”.

“I have been treated very well by HARCA in the decant and do feel gratitude for how they supported the move,” says Michael Newman now. He has resettled in Carradale House. “I am now happy where I live. I can see my old flat from the balcony of my new one, and I am starting a new life.”

So is Balfron Tower. Now that all tenants have been re-housed, physically and psychologically, Poplar HARCA has finally applied for planning permission for the refurbishment and has formed a partnership with developer London Newcastle to sell the flats.

What comes of all this? It’s astonishing that a social landlord started with the plan of refurbishing a listed building for its social tenants and found that it was able to do so only if it sold the building into private hands – while still being contractually obliged to carry out the work. Other housing associations may well be put off by this from pursuing such ambitious projects, and it is a shame, to say the very least, that Poplar HARCA, for all its achievements, could not set them a better example.