The current residents of Balfron Tower comprise a mixture of social rented tenants, leaseholders, private rented tenants, artists on live-work placements and property guardians. To understand why there is this diversity of residents it is necessary to look back historically.

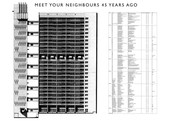

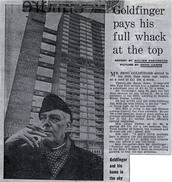

The tower’s 146 flats and maisonettes were first occupied by tenants of the Greater London Council (GLC) almost all of whom qualified for subsidised rent. These families used to live in the houses demolished to make way for the Blackwall Tunnel Approach roads and in accommodation deemed unsuitable, likely to have been damaged by the Blitz. The families were re-housed street by street, and only two came from outside of Tower Hamlets. Former neighbours were rehoused in flats sharing a common access gallery so as to maintain community spirit. Among this first crop of occupants were Ernö and Ursula Goldfinger, who lived in Flat 130 for two months from February 1968.

When ownership of the tower transferred from the GLC to Tower Hamlets Borough Council in the 1980s, these 146 residents became council tenants. Following the introduction of the Right to Buy, as part of legislation passed in the Housing Act 1980, some tenants took the opportunity to buy their flats from the council to become leaseholders. Some leaseholders live in their flats, some have moved and rent their flat out to private tenants.

In 2007, ownership of the tower passed to Poplar Housing and Community Regeneration Association (HARCA) under the condition they bring all dwellings in the estate up to decent homes standard as part of regeneration works. As a result of this change, council tenants became known as tenants on social rent or secured tenancy. When Poplar HARCA took over, 99 flats were occupied by tenants on social rent, 36 flats were owned by leaseholders and 11 were empty, though it is most likely that these were still allocated for social rent.

Since 2008, the tower has been designated 'decant status' to prepare for refurbishment works which require all residents to move from the building. As long-term tenants and leaseholders have moved, their flats have been occupied on a temporary basis by short-term residents under a number of different schemes; artists on live-work placements under Bow Arts Trust; short-life tenants with Phoenix Community Housing Cooperative; and property guardians with Dot Dot Dot and Ad Hoc. The precise numbers of residents in the tower under each temporary placement scheme have not been made publicly available.

In 2014 a number of cultural programmes took place in the tower. During these, contributing practitioners and visitors have stayed in the tower for short periods of time, either with artists on the live-work placement or in flats vacated for this purpose. For example, 45 volunteers to the British Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale stayed in the tower during a training week in April 2014, as did 10 architects during the International Architecture Showcase in June 2014. For RIFT’s site-specific Macbeth performance at the tower, audiences stayed overnight in empty flats from June to August 2014.

Refurbishment works will begin in 2015. Some leaseholders have agreed to pay a contribution to the works so they can return to their flats in the tower. The precise numbers of leaseholders that have elected to do so have not been made publicly available. No social rented tenants have been permitted to return to their flats in the tower. The remainder of the flats will be sold under Balfron Tower Developments, a joint venture between Poplar HARCA, United House Developments and Londonewcastle.

Throughout Balfron Tower’s 47 years of occupation there are very few publicly accessible accounts from residents.

During the public attention that surrounded Ernö and Ursula Goldfinger’s brief residency in 1968, a number of the first tenants were interviewed by national and international journalists, all of whom speak favourably of their new homes and communal life in the tower in spite of some early issues with draughty windows, lack of doorbells, and heating services that did not work properly. These many compliments and few snags are echoed in the interviews and notes available in the Goldfingers’ diaries and reports.

Some negative accounts begin to appear a decade later which coincide with a marked change in GLC policy on high-rise living, noting an increase in vandalism and anti-social behaviour. These negative attributes were exaggerated and embellished in the many films and TV dramas set on the estate in the following decades, which brought more immediate issues of intrusive filming schedules and unsightly leftover props.

Despite the renewed press attention that has accompanied recent plans for refurbishment, there is still a lack of residents’ voices, perhaps as many of them have already moved from the tower. A document that accompanied the stock transfer vote in 2006, stated that in Balfron Tower and neighbouring Carradale House, "consultation undertaken has shown that approximately half of the residents in the two blocks said that they would prefer to move out", which suggests approximately half would prefer to stay put - around 117 households between the two buildings. Without further information on this consultation it is difficult to discern the reasons underlying residents preference to stay or move. In accounts that are available (which includes oral history testimonies conducted in the last three years as part of this project, and which will be added to this website in full), current and former residents speak openly about the problems and joys of living in Balfron as the tower has witnessed wider changes in the area with the building of Canary Wharf and new populations.

The building's two lifts form the subject of most complaints, both of which were often faulty in the tower's early years, and never appear to have been quick or reliable enough. They stand for the lack of sufficient funds for repair and improvement that has afflicted the building in spite of decades of demands from residents, leading to concrete spalling, corroded wiring conduits, leaking pipes and vermin infestations. Long-term residents lament the closure of underground car parks, laundry rooms and communal spaces but observe that anti-social behaviour was curtailed by the installation of a door-entry system.

Residents also speak eloquently in appreciation of architectural details and collective experiences. This includes the well-proportioned flats, generous sense of light and space, and importance of the view that has become vital to their sense of belonging, identity and engagement with the city. For some, the tower's nine corridors encourage an unanticipated spirit of neighbourliness, a quality abundant in the Brownfield Community Cabin at the foot of the tower with its long-standing club and programme of activities, and particular praise is reserved for the community-spirited caretaker who tended to Balfron's spaces and residents with humour and devotion for a great period of the building's life.

Balfron Tower has historically divided opinion between those that view it as a thrilling building with carefully crafted detailing and egalitarian ideals, and those that view it as too forbidding to be suitable and sociable.

Throughout the shifting course of opinion, both expert and popular, certain judgements of Balfron Tower have been accepted uncritically – correlating its architecture of dramatic proportions with a way of life as stark and severe, ill suited to the needs of families and at a high density in which socialisation is difficult. The majority of these judgements appear not to have been informed by resident testimony that can speak with personal experience of the social relations and communal interactions the tower has generated.

Architectural historians have long admired the image and ideals of the tower, though their accounts also tend to lack a voice from residents. The tower’s popularity has grown as post-war architecture has been reappraised in the last decade, spurring a flurry of new press and blog articles. These vary from well-researched accounts to a remarkable number of ill-informed and inaccurate accounts that disagree on simple details - Balfron’s height, age, and even name.

Balfron Tower has been the setting for the films 'Shopping' featuring Jude Law, 'Greenwich Mean Time' with Chiwetel Ejiofor, '28 Days Later' by Danny Boyle and 'Blitz' starring Jason Statham; TV dramas 'Hustle', 'Fixer' and 'Whitechapel'; the video to Oasis' 'Morning Glory'; and is purported to form the inspiration of JG Ballard’s novel 'High Rise' with an architect who lives in the penthouse. Residents on the Estate Board recently stopped plans to film Brad Pitt’s 'World War Z'. Balfron’s representations notably go beyond typical kitchen sink dramas set in housing estates to fictive dystopian wastelands of feral gangs and zombies.

Tower Hamlets Film Office markets seventeen of the Borough’s public housing estates as potential film locations. It promotes concrete walkways, ‘imposing’ towers, ‘highly visible examples of Brutalist architecture’ and underground car parks that offer ‘self contained urban, gritty location[s]. Gloomy light, rich textures and a littered dusty environment creat [sic] fantastic atmosphere.’

Listing is a way of recognising and protecting when a building is of special architectural or historic interest. Listing does not mean that a building cannot be changed, but it does mean that consideration needs to be given to make sure that any changes do not diminish this special interest. Anyone can suggest a building for listing. Historic England (the public body formerly known as English Heritage) will examine the case and put forward recommendations to the UK Government’s Department of Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) which makes the listing decision.

Balfron Tower was listed Grade II in March 1996.

In the 1996 listing description, English Heritage identify Balfron as a "well planned and beautifully finished" tower with a "distinctive profile that sets it apart from other tall blocks" accommodating marble and tiled interiors that are "unusually well thought-out", "revealing Goldfinger as a master in the production of finely textured and long-lasting concrete masses."

In August 2014, I worked with James Dunnett of DOCOMOMO to write a listing upgrade nomination for all of Ernö Goldfinger's buildings and spaces at the Brownfield Estate.

Balfron Tower was upgraded to Grade II* in October 2015.

Historic England and the Department for Culture, Media and Sport accepted our bid and upgraded Balfron's listing to Grade II* and Glenkerry House to Grade II. In the updated listing description, Historic England state: "Balfron Tower was designed as a social entity to re-house a community, according with Goldfinger's socialist thinking.” And among their ‘principal reasons' for listing, they note: “Architectural interest: a manifestation of the architect’s rigorous approach to design and of his socialist architectural principles” and "Social and historic interest: designed to re-house a local community”.

Our reasons for the nomination include:

- Goldfinger’s buildings and spaces on the Brownfield Estate are already protected by the Conservation Area, but only Balfron Tower and Carradale House are listed. All of these should be listed at the same level of listing as Trellick Tower in North Kensington, including specifically the spaces between the buildings which can be vulnerable to development pressures, to recognise the exceptional architectural qualities of Goldfinger's work on the estate.

- A Grade 2* level of listing would ensure that Historic England was actively involved in assessing any application for listed building consent for alterations or additions of any kind (which otherwise would be at the discretion of the local authority) and could make additional funding available via Historic England and might perhaps make it more possible for DCMS to help funding for refurbishment within the social housing sector.

- The current listing descriptions of Balfron Tower and Carradale House are inadequate and should be elaborated on to include all their ancillary buildings, reflect the social elements in the design and preserve the social purpose of this housing.

In support of this final point I produced a supplementary document devoted to residents’ experiences, drawing from residents’ own words to identify the aspects of the building they cherish and convey how unique design features have framed their everyday experiences. Owen Hatherley wrote a statement in support of the listing upgrade.

Balfron is commonly referred to as the ‘sister’ or ‘twin’ to Trellick Tower. The distinctive profiles of the two high-rises are often mistaken for one another, but it is useful to identify distinctions in the buildings and how their residents have fared.

Geography: The two towers are said to ‘book-end’ London; In the East End, Balfron Tower marks the eastern edge of the Brownfield Estate in Poplar, beside the Blackwall Tunnel approach road; in the West End, Trellick Tower marks the northern point of the Cheltenham Estate in North Kensington, close to the elevated Westway dual carriageway.

Age: The London County Council (LCC) appointed Ernö Goldfinger to a list of approved architects for the council’s housing schemes in 1961. They commissioned him to design a housing estate in Poplar which he developed from 1962-3 into the 26-storey Balfron Tower, built in 1965-7.

In 1966, the Greater London Council (GLC) had replaced the LCC, and commissioned Goldfinger for another housing estate in Kensington which included the 31-storey Trellick Tower, built in 1968-72.

Neighbouring buildings and spaces were added to the two sites by Goldfinger in subsequent years; two further phases of the Brownfield Estate in Poplar were built from 1967-75; the rest of the Cheltenham Estate in Kensington was built from 1969-73.

Design: At first glance the buildings appear to be very similar. Their silhouettes are defined by separate circulation towers joined at every third floor by communal walkways and topped with projecting boiler rooms.

Externally, the main difference is that Trellick Tower is four storeys taller than Balfron and with a slimmer circulation tower that has been rotated ninety degrees. These two changes lend Trellick a more elegant profile. Trellick is also linked to a seven storey ‘Block B’ where shops were located on street level.

Internally, Balfron comprises 146 flats and maisonettes, significantly fewer than Trellick’s 212. Trellick has the benefit of three lifts and slightly wider flat layouts with cedar-clad balconies spanning the entire width, not halfway as they are at Balfron. There are also changes in its detailing such as windows that swivel into the room for easier cleaning.

It is often stated that, from his experience of living in Balfron Tower for its opening two months from February 1968, Goldfinger made design alterations to Trellick. However, given the overlap in commission, design and build dates for the two towers, it is not clear whether there would have been sufficient time for Goldfinger to implement any significant changes based on his empirical and experiential research. Instead, it is likely that modifications were made to Trellick from the experience of constructing Balfron.

Residency: Goldfinger always maintained that he designed his social housing ‘for himself’. While Goldfinger’s ‘sociological experiment’ at Balfron Tower is well known, his penchant for tasting his own cooking did not end there. He moved his own architectural practice into Block B, linked to Trellick Tower, from 1972 and was a daily visitor until retirement in 1977.

History: Residents in both towers have endured difficult periods from the late 1970s, but Trellick seems to have particularly suffered. It became known as ‘The Tower of Terror’, gaining a reputation for vandalism and crime, which mainly involved drug-dealing and drug-taking, but also included instances of sexual assault, prostitution, muggings, break-ins and rough sleeping. Like at Balfron, the installation of a door-entry system curtailed much of the anti-social behaviour and the tower became a cult landmark by the 1990s.

Listing: Balfron Tower was awarded a Grade II listing in March 1996 and its neighbouring Carradale House was also listed at Grade II in December 2000. The rest of Goldfinger’s buildings and spaces at the Brownfield Estate are already protected by a Conservation Area but are not yet listed.

Trellick Tower was granted Grade II* listing in December 1998 and the rest of the Cheltenham Estate was listed at Grade II in November 2012.

Representations: Many films and TV dramas have used Balfron and Trellick Tower as filming locations, though Trellick is notable for featuring in many music videos, and can even boast a reference in the lyrics of Blur’s 'Best Days' and Emmy The Great’s 'Trellick Tower'.

In the film 'Shopping', shot at Balfron Tower, Sean Bean arrives for a brief cameo in a black Mercedes. "Look at this place," he mutters to his driver. "How do people live in this filth?" He walks along a ground floor corridor completely blanketed in graffiti, "This whole estate’s a disgrace."

In TV drama 'The Bill', the camera pans up Trellick Tower as a character asks, "Who’d want to live in that hell-hole?" Twenty-five of Trellick’s residents wrote in to the programme to reply, "We do."

Refurbishment: Both towers require internal and external refurbishment works. These are scheduled to begin at Balfron in 2015 by a joint venture between Poplar Housing and Regeneration Community Association (HARCA) and two private developers, Londonewcastle and United House Developments.

Residents: The majority of flats at Trellick Tower are occupied by households on social rent - one recent blog states this is the case for 181 of the 217 flats, though I have not been able to cross-reference this fact. Similarly, according to different sources, between 99 and 110 of Balfron’s 147 flats were designated for social rent when the Poplar HARCA took over in 2007. However, following refurbishment works, no social rented households will be permitted to return to Balfron Tower.

Balfron Tower is currently owned and managed by a housing association, Poplar Housing and Regeneration Community Association (HARCA). This will change when refurbishment works have been approved as Poplar HARCA have formed a joint venture partnership with two private developers. Preceding this, there have been three previous changes of ownership between public administrations. The consequence of each of these five changes are significant. Each owner appears to have, at one stage, scheduled major refurbishment works to the tower but which have subsequently been shelved as the ownership has changed hands.

The tower was commissioned by the London County Council in 1963. This municipal body was replaced by the Greater London Council (GLC) in 1965, the year construction started on the tower.

The GLC remained the owner from the completion of the tower in 1967 until the 1980s. To prevent the rents of GLC dwellings being raised in 1968, Tower Hamlets Borough Council unsuccessfully requested the transfer of all the GLC's housing within the Borough.

Ten years later, in 1978, Balfron Tower was still under the ownership of the GLC when the tower was earmarked to join a GLC pilot scheme providing a ‘facelift’ to two high-rise blocks nearby in ‘an attempt to improve the quality of life for tenants who live in tower blocks’. I have yet to find evidence whether these works took place at Balfron.

The main stock transfers from the GLC to Tower Hamlets eventually took place in 1980 and 1981, but because of the sheer number of council homes, a delayed transfer took place on 1 July 1985. Following the transfer of all the GLC housing stock to the council, Tower Hamlets became the landlord of eight out of every ten homes in the Borough.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Tower Hamlets worked with independent architects to develop plans to improve access routes and security including a proposed new concierge building to be shared by Balfron Tower and Carradale House, but which were cancelled when stock transfer plans were first suggested.

In 2007, ownership of the Brownfield Estate was transferred from Tower Hamlets to Poplar Housing and Regeneration Community Association (HARCA). This followed a vote the previous year when 78.8% of tenants and 32.5% of leaseholders of of three estates - Teviot, Brownfield and Aberfeldy - voted in favour of a stock transfer under the condition Poplar HARCA bring all dwellings in the estate up to decent homes standard as part of regeneration works.

Poplar HARCA remain sole owners of the tower, but in December 2014, Balfron Tower Developments, a joint venture between Poplar HARCA, United House Developments and Londonewcastle, was created to regenerate the building. These regeneration works are scheduled to begin in 2015.

Social rented tenants are not permitted to return to their flats in the tower following the refurbishment works. Leaseholders have been advised that "they will able to move back to Balfron Towers once the works are complete, providing they are able to pay their share of the refurbishment costs as required under the terms of the lease agreement. The terms of the current lease obliges the landlord to recharge the costs of any major works to the block to leaseholders."

Before the stock transfer vote in 2006, residents of the 146 flats of Balfron Tower and 88 flats of the neighbouring Carradale House were sent consultation documents, transfer agreements and a redevelopment video proposing that approximately 130 flats between the two buildings would be sold on the open market but that existing residents would have a "real choice" over their homes, creating "a mixed community within these buildings", "a mixed community of people who want to live in them". These documents can be viewed below. The Estates Offer stated that, in Balfron and Carradale, "consultation undertaken has shown that approximately half of the residents in the two blocks said that they would prefer to move out", which suggests approximately half would prefer to stay put.

In the years that followed the stock transfer vote, the option for social rented tenants to return to their flats following the refurbishment works changed. Tower Hamlets contended, "the global financial downturn is also having an impact on the deliverability of certain aspects of the scheme due to provide the required cross subsidy. Poplar Harca has been looking at alternative solutions and funding models to ensure they are able to achieve the promises made in the offer document."

From October 2010 to December 2014 Poplar HARCA publicly stated that it is "possible but not probable" that tenants will have a right of return. There appears to be a distinction between this statement repeated publicly and the organisation’s confidential financial viability documents and internal annual reports that attest, from August 2012, that "Balfron will become a leaseholder-only block" and converted "from a social rented block to all private sales".

Without any proposed flats on social or affordable rent, the commitment to creating a mixed community in the tower as a result of regeneration works also appears to have changed.

There is some information regarding where social rented tenants moved to but no information regarding leaseholders.

In terms of the former, Poplar HARCA have stated, of the 102 of the social tenancies in Balfron Tower, "71 of the households moved to other Poplar HARCA homes locally within E14. In fact 10 moved just next door to Carradale House. 18 remained locally within Tower Hamlets having successfully bid for social tenancies in E1, E2 and E3 which are only a ten minute bus ride away."

Of the 71 households that moved within E14, 10 moved to Carradale House but it is unknown how many moved to other buildings within the Brownfield Estate.

18 moved to postcodes E1, which is around Whitechapel, E2, which is around Bethnal Green, and E3, which is around Bow.

Poplar HARCA have not made available details of where the other 13 households on social rent moved to.

It isn’t possible to fully answer this question from the documents currently available.

In response to this question, which I asked in December 2014, Poplar HARCA answered: "we've increased the number of social rented homes in Brownfield and across Poplar."

This does not appear to address the precise question posed, so I have looked at publicly accessible documents for more detail.

The stock transfer document which set out the regeneration works in 2007 states that "overall there will be no loss of homes for rent on the Brownfield Estate." It does not state which type of rent - social, affordable or private.

Based on the public information to hand, I have been able to calculate there will be a net loss of between 42 and 83 social rented homes within the Brownfield Estate.

This calculation is based on the following:

The Brownfield Estate

The Brownfield Estate comprises the following blocks:

- Balfron Tower 1-146 St Leonards Rd;

- Brownfield St 1-43 (Odds); Brownfield St 132-154 (Evens); Brownfield St 2-60 (Evens); Brownfield St 45-107 (Odds); Brownfield St 62-128 (Evens);

- Burcham St 2-24 (Evens); Burcham St 26-46 (Evens); Burcham St 48-94 (Evens)

- Carradale House 1-88 St Leonards Rd

- Langdon House 1-45 Ida St

- Lodore St 2-72 (Evens)

- St Leonards Rd 52-74 (Evens); St Leonards Rd 27-39,27-35a,63-75,63-73a; St Leonards Rd 41-53,39-53a,77-89,77-89a; St Leonards Rd 19-25,19a-23a,55-61

- Willis St 54-112 (Evens); Willis St 6-52 (Evens)

Planning documents from 2011 identify the freehold of 669 of the Brownfield Estate’s 800 dwellings are owned by Poplar HARCA. Of these 669, 463 are tenanted, 206 are leasehold.

There are no further records I have been able to source of numbers in each of the blocks of that comprise the estate. In any case, these figures are likely to have changed since Poplar HARCA took over because of tenants taking up the newly incentivised Right to Buy as discounts were increased in 2012 and 2013.

The only blocks that have been identified to face significant changes of tenure because of refurbishment works are new homes built on the estate, homes demolished to make way for these new builds, and Balfron Tower and Carradale House which were always singled out for changes because of their Grade II listed status. I will take each of these in turn.

New homes on the estate

New homes built as part of the regeneration works on the Brownfield Estate:

- 25 new homes for social rent were added in infill blocks built between existing blocks on the estate,

- 32 new family sized houses and flats for social rent were added in Ida & Follett Street.

- 22 family sized flats for shared ownership were added as part of the Panoramic building’s 112 homes, but whilst these are within the affordable homes bracket, they are not the same as social rent.

So there has been an addition of 25 + 32 = 57 social rented homes and 22 affordable homes.

Demolition to make way for new homes on the estate

To make way for these new builds homes, three sites containing homes were demolished; incorporating 15 rented studio flats, 13 rented one-bedroom units and 2 private one-bed units. This is a loss of 30 homes, but the tenure mix of these homes is not stated on the documents available.

So the net addition of new build socially rented homes is 57 - (up to 30) = between 27 and 57 social rented homes.

The tenure mix in Balfron Tower before regeneration works

In a recent email, Poplar HARCA state, of Balfron Tower’s 146 dwellings, 102 were designated on social rent when they took over in 2007. This figure differs from that identified in a subsequent Freedom of Information request which states there were 99 households on social rent and 11 flats void. These 11 flats are likely to have been designated for social rent but, at that time, were unoccupied. No further figures are available.

So there were 99, 102 or 110 social rented households in Balfron Tower in 2007.

The tenure mix in Carradale House before regeneration works

According to the listed building application in 2010, Carradale House comprises of 88 dwellings, of which 20 are owned by leaseholders, which leaves 68 social tenancies. It goes on to state that the development proposals do not seek to alter any aspect of the tenure of the block.

So there were, and will be, 68 social rented households in Carradale House.

The tenure mix in Balfron Tower and Carradale House before regeneration works

So there were (99 to 102 to 110) + 68 = between 167 and 178 social rented households between the two blocks before regeneration works.

The tenure mix in Balfron Tower and Carradale House following regeneration works

Internal financial documents and confidential viability reports state Balfron Tower will be turned into a leaseholder-only block, so it will lose between 99 and 110 secure rented homes because of this.

Poplar HARCA state 10 secure tenants moved from Balfron Tower to Carradale House during the refurbishment works. Planning documents claim Carradale House will not alter any aspect of tenure, so there is no change to the 68 social tenancies in the block in spite of this move.

So there is a loss of between 99 and 110 social rented households from the two blocks.

Overall figures following regeneration works

To take the conservative estimate for each figure, and assume no social rented homes were demolished to make way for new builds, there will be:

a net loss of 99 - a net addition of 57 = a total loss of 42 social rented homes

To take the upper estimate for each figure, and assume all the homes demolished were on social rent, there will be:

a net loss of 110 - a net addition of 27 = a total loss of 83 social rented homes

As previously stated, the transfer document states that overall there will be no loss of homes for rent on the Brownfield Estate. It does not state which type of rent - social, affordable or private. If it does refer to social rented homes, there is a shortfall of between 42 and 83 homes across the estate which should be designated for social rent.

Please note these calcuations are a work in progress as complete figures have not yet been made available.